A Vision for Data in a Non-Data (Focused) Company

Before I begin, this is not meant to be a criticism of any company I’ve worked with or for. This is a mission and vision statement for my idealized data organization within a broader company, one not focused on data and data products as its primary deliverable. This is simply my view of where it should be, and how it should be deployed.

Almost everybody has heard the now cliché phrase, “Data is the new oil.” I’ve always felt uncomfortable with that statement, for a variety of reasons.

Data is not oil.

Data is an accelerant.

It makes processes move faster, makes tedious and difficult tasks easier, and enables us to do things we couldn’t do on our own before. A smart person with an understanding of data is able to do so much more today, through good management and usage of data, than their data-illiterate peers. The real question, and I’ve seen it asked dozens of times, is where and how data should live within a larger organization.

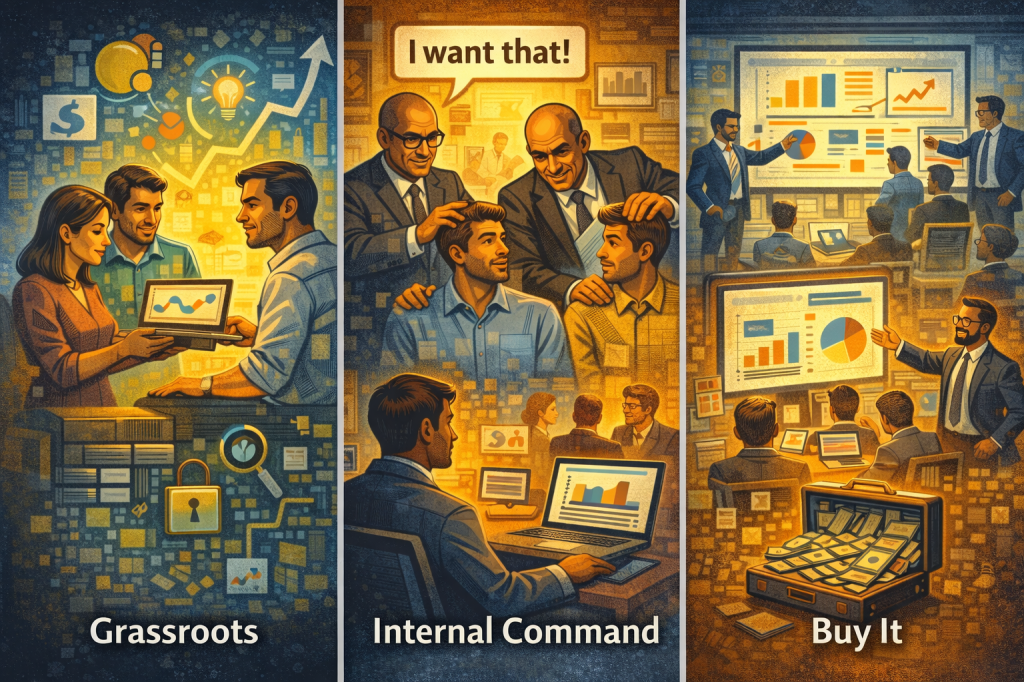

In my experience, data teams usually begin in one of three ways. Often, all three happen at once.

Grassroots and Organic:

A few forward-thinking people decide to investigate how they can apply data science principles to their own jobs to make themselves more efficient. There’s an addictive quality to it. With a little extra work up front, they realize they can save enormous amounts of time downstream and make better decisions more quickly. Their productivity catches the eye of leadership, who ask them to focus more on those deliverables, and a nascent data group forms.

Internal Command:

Management looks over the fence and says, “I want that,” and forces the creation of a data team by tapping people with identified potential on the shoulder, giving them space and resources to learn and grow.

Buy It:

Management sees the writing on the wall and brings in consultants to deliver high-value data projects. The people who manage those consultants become the de facto data group.

What usually happens, particularly in the first two scenarios, is that this team starts building things that are clearly valuable. They partner with people across the organization and deliver real results. At this point, it barely matters where they sit structurally. They are turning the first page in the data story.

Then something interesting happens.

They start spreading their knowledge. Show-and-tells. Lunch-and-learns. Mini seminars. Informal training. Your staff aren’t blind. They see the cool things happening, and many of them want in. Even those who don’t believe they have the necessary skills are curious.

The data group becomes the centre of a quiet productivity revolution. They become a natural hub, and colleagues in other teams become spokes.

Usually at this point the data team gains autonomy. Instead of being side-of-desk work, it becomes a recognized function. Now they start building bigger and better. Instead of isolated tools and one-off databases, they move to centralized platforms, shared environments, version control, and architectures that allow data to be accessed with permissions, alongside notebooks and code that formalize knowledge and speed up learning.

This is a huge leap forward.

There are, however, a few things to watch out for.

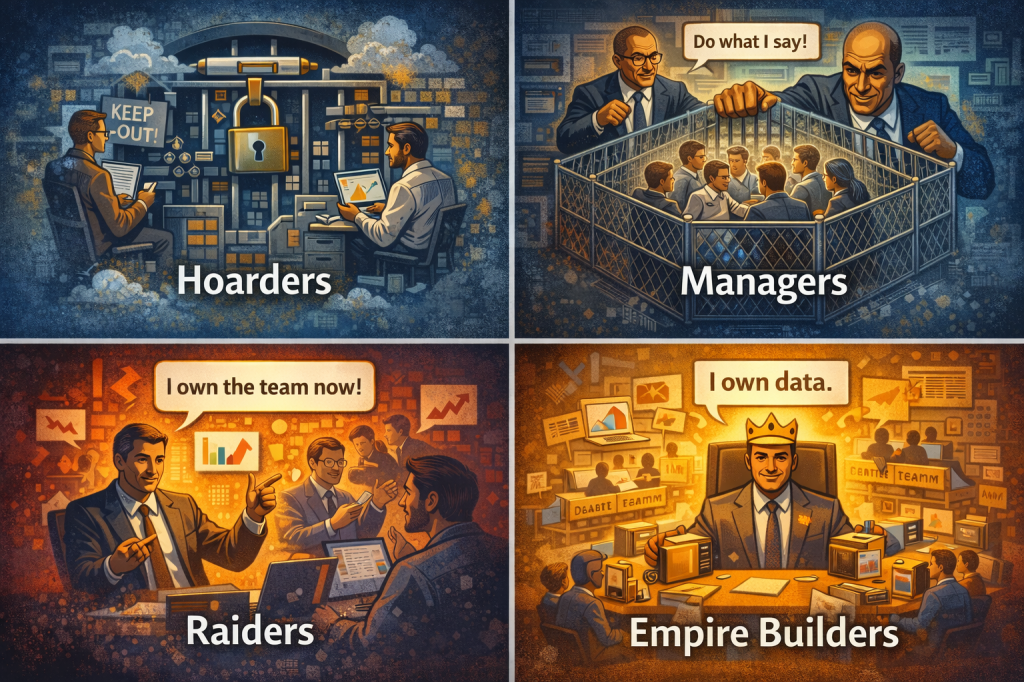

Data Hoarders.

These believe data must be protected at all costs. Even data provided by other teams should be locked away, lest someone draw an incorrect conclusion. I like to counter this by cultivating humility. Anybody should be able to explore non-sensitive data. When they think they’ve found something, approach it with: “I think I found something. Can you check my findings?”

Empire Builders.

Some people believe they own “Data and Analytics.” A favourite quote from a former manager was: “We can no more claim to own data science than we can claim to own mathematics.” That always resonated with me. Locking data science inside one team simply guarantees that smaller data groups will pop up elsewhere.

Raiders.

Closely related to empire builders. They see the success of the data team and want that credit themselves. They argue it belongs under their organization, undermine wins, and eventually force it under management that often does not truly understand the work. Natural growth usually slows dramatically at that point.

Managers.

Managers want to corral all the talent inside their team so they can focus on their priorities and nothing else, or as little as they can afford while maintaining the pretense of a central storage area

Assuming you’ve managed to avoid hoarders, empires, managers, and raiders, you now have the roots of a data organization. You have the Lego pieces. The next question becomes structure.

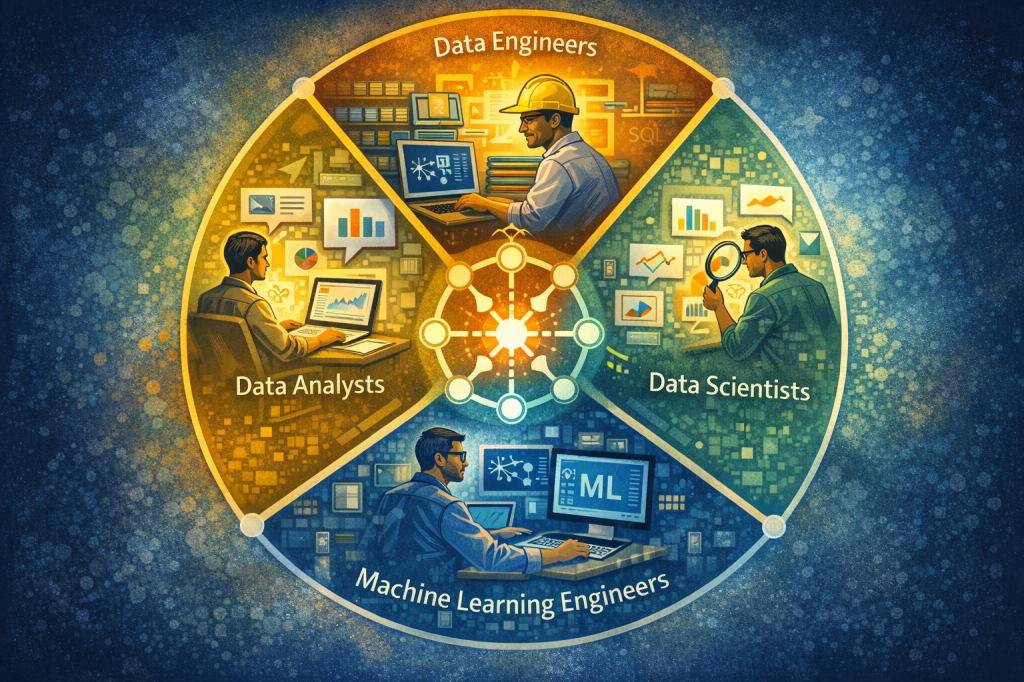

First, you have to realize that “data” isn’t a job.

There are several distinct roles required for a functioning data organization. Smaller companies often rely on one person doing a bit of everything. Larger ones need specialization.

Data Engineers are the plumbers and foundation builders. They forge pipelines, centralize data, connect APIs, write ungodly SQL, and build the systems everything else depends on. Their work is deeply appreciated by technical users and frequently invisible elsewhere.

Machine Learning Engineers build models and MLOps systems that bring those models into production. Their work is often misunderstood and assumed to be automatic.

Data Scientists are the experimenters. They turn high-quality data into predictions and prescriptions that guide decisions. Their work is often viewed as expensive or risky.

Data Analysts package all of this into stories stakeholders can consume. They visualize complexity. Because their output is visible, they are often the ones rewarded, despite standing on a large iceberg of upstream work. (Good ones make sure they credit the other specialties.)

All of these skills are necessary.

Now, where should this group sit?

Honestly, it matters less than people think.

What matters is that they have some independence, can weigh priorities across the organization, and are led by someone who is not a hoarder, empire builder, manager, or raider. They must be given enough rope to fail. Some experiments will not pan out. That is the nature of experimentation.

They also need freedom to work directly with others. Some of the best projects I’ve worked on started from something as innocuous as a locker-room conversation before a hockey game. One small chat turned into multi-million-dollar savings. That only happens when people are free to learn and explore together.

Data is not something to be owned. It is something to be shared, taught, and cultivated.

This connects directly to one of my personal pet peeves: “Innovation Teams.”

Companies want to be more innovative, so they create an Innovation Team. Those people are now officially tasked with innovation. The unintended consequence is that everyone else quietly learns they are no longer responsible for it.

The same thing happens with data.

If analytics is defined as something one team does, everyone else disengages. Learning stops spreading. Curiosity narrows.

The data team should instead be a centre of learning. They do some projects themselves, especially the technically hardest ones, but they also provide tools, platforms, data, and training so others can work with data too.

They enable.

A well-rounded, independent centre of learning. A shared resource for growth. A force multiplier.

That is the ideal data organization. It is the environment every data professional I know wants to work in.

And it is the most reliable way I’ve seen for data to truly accelerate a business.

I love teaching people how to “data.” One of my favourite stories was a new grad that came onto my team without any coding experience, and six months later, moved on saying, “I can code now, how cool is that?” Very cool, and now, she can develop tools and understands more of the possible, benefiting her new team as well.

Feel free to post your thoughts. Tell me your perspective in the comments!

Leave a comment